When you are designing for any medium – not just the web – the way you use color in your designs will impact how that design is perceived, understood and interpreted. It’s important to remember that color brings out emotions (good and bad) both in people and in culture.

Largely tying into your research phase, it’s wise to ensure that you understand your target audience and how color affects them. Then you can help cater the website’s design and how the website looks and feels through the clever use of color.

Before you can start working with color in your designs, you should understand more about what color is. That can sound pretty ridiculous – of course you know the difference between pink and blue – but really it’s more about understanding the difference that color can make in design; how color evokes feelings within a person or culture and how color can be used effectively in your designs to help make better experiences for your users.

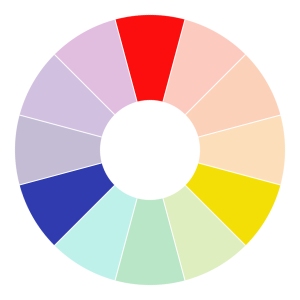

The Color Wheel

A color wheel is a diagram which shows the main color hues and how those colors relate to each other. The most common color wheels feature six or twelve colors.

The main colors of the wheel (red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet) are featured on both wheels, with the potential addition of six extra colors (red-orange, yellow-orange, yellow-green, blue-green, blue-violet and red-violet).

As you can see, all of the extra colors on the larger color wheels relate to the main colors that are already there – effectively, they’re “in-betweens” of the original colors themselves.

Primary Colors

You’ll probably recognize these as being the three primary colors: red, blue and yellow.

Primary colors are the base colors of any color wheel and of the color spectrum as a whole. To create any other color, you’ll have to use a combination of two or all three of the primary colors.

Secondary Colors

These are purple, orange and green.

Secondary colors are created when you mix two primary colors together. These also lie directly opposite the primary colors on the color wheel, as they are in-between the two colors that have been mixed to make this secondary color.

Note: We refer to these opposing, contrasting colors as beingcomplementary – when mixed, these complementary combinations (such as red + green) produce a neutral color.

Tertiary Colors

Tertiary colors are created when you mix one primary and one secondary color together. As such, there are more tertiary colors than primary or secondary, owing to more combinations which can be made.

On the color wheel, these lie between each of the primary and secondary colors.

Color Families

When I think of color, there are two main elemental families that stick out to me – warm colors and cool colors. A little tip that makes it easy to decipher which colors belong to which family, is to split the color wheel in half.

Warm Colors

Colors that belong to the warm family are colors such as reds, oranges and yellows. These all evoke a feeling of warmth in some way – red is passionate and fiery, and orange and yellow are summery, like the sun.

Cool Colors

Colors that belong to the cooler family are the blues, greens and purples of the color wheel. These naturally evoke a calmer feeling than the other colors, they’re more subdued than warmer colors, linking more closely to water, nature and such.

Color Meanings

First up, it’s a good idea to start learning about what each of the main colors mean. It’s important to remember that every color will have a different significance depending on the person you talk to and wherever you are in the world. Don’t forget that as well as the broader population, colors often have personal meanings to individual people or groups. This means that although the classic (or assumed) interpretation of that color may mean one thing, how an individual interprets that color may be completely different.

In web design – or any design, really – you can never afford to make rigid assumptions about your users. However, color is one area where there’s a little exception to be made. As color evokes personal meanings to every individual, you have to try and go with the broader assumption of what a color may mean to your target audience – unless you’re lucky enough to have more tailored research and information that lends itself to choosing color palettes in your project.

You also need to think about how your color will be used – both in a practical sense on the web, but also physically by those who will actually be using your website. Think about accessibility and how these colors could be perceived or seen by those with color-blindness or other visual difficulties. Although it’s impossible to know what difficulties every user will have (and even if you did, there’s no way to design to cater to them all) you can take action to use color effectively but in a way that doesn’t cause further problems for a portion of your users.

Further Reading

Geri Coady wrote a brilliant little book on Color Accessibility and goes into a lot of detail on building color accessible websites. It’s definitely worth a read to extend your color accessibility knowledge.